Glen Pass Guide: Approaches, Crossing, and Snow

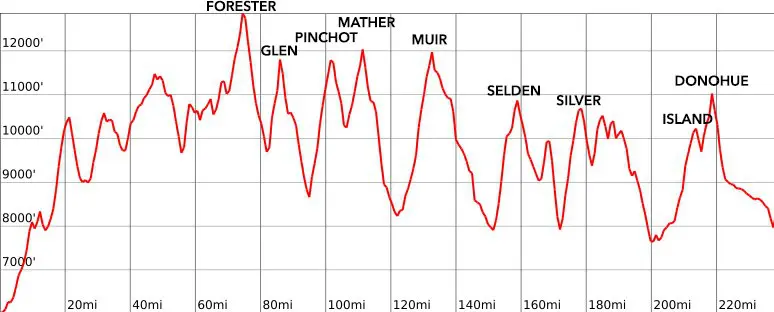

Glen Pass, the 11,969 ft / 3,648 m pass named for Forest Service ranger Glen H. Crow, is the second Sierra pass encountered by northbound Pacific Crest Trail (PCT) thru-hikers and the eighth encountered by southbound John Muir Trail (JMT) hikers.

It’s located 11.6 miles / 18.67 kilometers north of Forester Pass and 16.1 miles / 25.91 kilometers south of Pinchot Pass. Glen Pass is not only popular with PCT and JMT hikers, but also with hikers heading to Rae Lakes (north of the pass) by way of either Onion Valley (via Kearsarge Pass) or Road’s End.

There is a ranger station on either side of Glen Pass, one located at Charlotte Lake and the other at Rae Lakes. It’s part of the Pacific Crest Trail, John Muir Trail, Southern Sierra High Route, and Rae Lakes Loop (which is the reason it’s more popular than the neighboring Sierra Nevada passes to the north and south – Forester and Pinchot).

Glen Pass Stats

- Height: 11,949 ft / 3,642 m

- Location: Kings Canyon National Park, Sierra Nevada, California, USA (36.789431, -118.413432)

- Approach from the south: 4 mi / 6.44 km gaining 2,421 ft / 738 m from Bubb’s Creek

- Approach from the north: 8.7 mi / 14 km gaining 3,402 ft / 1,037 m from Woods Creek

- Nearest road access: Kearsarge Pass Trail to Onion Valley Campground (to south)

- Part of the: Pacific Crest Trail, John Muir Trail, Southern Sierra High Route, Rae Lakes Loop

- PCT Northbound Mile: 791.1 (1,273.2 km)

- PCT Southbound Mile: 1,862 (2,996.6 km)

- JMT Northbound Mile: 33.1 (53.3 km)

- JMT Southbound Mile: 177.3 (285.3 km)

Glen Pass: The South Side

The southern approach to Glen Pass begins at the junction of the Bubb’s Creek Trail (leading west to Road’s End in Kings Canyon National Park) and the Pacific Crest Trail/John Muir Trail (coming north from Forester Pass – or Junction Pass if you’re on the Southern Sierra High Route).

From the south, it’s one of the shortest Sierra pass approaches on the PCT or JMT, covering just 4 miles / 6.44 km, with a gain of 2,421 feet / 738 meters (coming out to 605 feet per mile / 114.6 meters per kilometer). Kearsarge Pass, a 7-mile / 11.3 km one-way detour to Onion Valley Campground, is a popular resupply spot for PCT hikers. The entirety of the route over Glen Pass (from Bubb’s Creek to Woods Creek) is also part of the Rae Lakes Loop, beginning and ending at Road’s End.

Heading north from Bubb’s Creek, the trail climbs with a great view of East Vidette and flattens out as it passes the first trail for Kearsarge Pass via Bullfrog Lake. Then, it passes the junction for Charlotte Lake (and a ranger station) to the west, where there’s a second trail leading to Kearsarge Pass to the east.

Continuing north, the trail contours around the mountainside before leveling out a bit and passing a few small tarns. Hikers then reach a slightly larger lake (pond? big tarn?) where it’s probably wise to fill up on water if you’re feeling thirsty. After one more climb, you’re in view of the pass and one more lake (but it’s a bit of a drop to it).

The top of the pass is on the smaller side and is more similar to Mather or Forester Pass than it is to the wide and broad passes like Muir or even Pinchot – you probably wouldn’t want to camp up here (there are camping opportunities along the trail to the south and at Rae Lakes to the north). The views from the top are excellent, with Diamond Peak, Black Mountain, and Rae Lakes dominating the view to the north.

Glen Pass: The North Side

The approach to the north side of Glen Pass starts at the Woods Creek Suspension Bridge (possibly the single most significant piece of backcountry infrastructure in the Sierra, besides the trails themselves). From the bridge, the trail heads 8.7 mi / 14 km over 3,402 ft / 1,037 m (391 ft per mi / 74.1 m per km) up the South Fork Woods Creek toward Rae Lakes.

On the way, you’ll pass Dollar Lake and Arrowhead Lake before making the final climb up to Rae Lakes, where there is a ranger station and a developed campsite (complete with bear box). From Rae Lakes, you can also access the Sixty Lake Basin to the west and/or make a short trek up to Dragon Lake to the east. Rae Lakes is a popular destination for hikers, and it might be nice to have alternatives if you’re looking to escape any crowds.

Passing Rae Lakes, the trail begins the first of two climbs, each steeper than anything found between Rae Lakes and Woods Creek. There’s a spot between the two – before beginning the ascent of Glen Pass’s northern headwall, where the trail momentarily flattens out and you get a good view of the climb up to the pass.

The north side of Glen Pass is steep – ascending around 600 ft / 183 m in just about 0.55 mi / 0.89 km of trail (if you’re hiking in snow-free conditions). If you’re hiking up (or down) this section in the snow, you can expect to find a challenge. I found the north side of Glen Pass to be one of the sketchiest sections of the entire Sierra portion of the Pacific Crest Trail, particularly when crossing in the snow (I descended the northern side).

Glen Pass in the Snow

Crossing Glen Pass in the snow is a challenge. I consider it one of the most difficult Pacific Crest Trail Sierra passes. Both the south and north sides of the Glen are steep and will probably require the use of some traction and an ice axe by most hikers (I used mine on the north side only, but it wouldn’t have hurt to use them on the south side of the pass, too).

On the southern side, the traverse around the mountainside and the traverse to the base of the pass require you to pay careful attention to your route, as they can be steep and icy. The climb up the south side of the pass is short but steep – the northern side is just as steep but even longer (so prepare yourself for a moment of “are you serious?” once reaching the top if you’re heading northbound).

If you’re not comfortable with what could be an epic glissade (heading northbound), you’ll need to carefully switchback your way down the northern side of Glen Pass. This is one of the few places I used my traction and an ice axe in the Sierra, and what I’ve previously described as one of the sketchiest Sierra passes on the Pacific Crest Trail.

The best part of Glen Pass in the snow is that the approaches aren’t terribly long (the 8.7 mi / 14 km northern approach is over twice as long as the southern approach, but most of it is below 10,000 ft / 3,048 m). Once you reach Rae Lakes, the trail relaxes a bit (even in the snow), but it takes some effort to get down to (or up from) the lakes in the first place.

According to my GPS, the track recorded over Glen Pass in the snow was 0.8 mi (1.29 km) shorter than that in dry conditions (13.4 mi [21.57 km] vs. 12.6 mi [20.28 km]) – traveling from Bubb’s Creek to Woods Creek. However, as expected, the time it took to navigate this section in the snow was significantly longer than in dry conditions.

Glen Pass Gear

I used my microspikes and ice axe (not snowshoes) for the northern side of Glen Pass, but not the southern side. That said, I was with other hikers who used their gear on the south side, and I was with one hiker who didn’t use any gear for either side (that said, I think he was happy to have us going ahead of him and kicking steps).

If you’re interested in what snow gear Pacific Crest Trail hikers liked best during their thru-hikes, you can find out more at the PCT Gear Survey.

Map and GPS Track

Conclusion

Glen Pass is an unassuming yet challenging Sierra pass. In dry conditions, it’s a quick 4 mi / 6.44 climb up to the top, but this can take significantly more time in the snow.

It’s one of the most popular passes (in terms of the number of people crossing it) on the Pacific Crest Trail and the John Muir Trail because it is also a part of the popular Rae Lakes Loop (and from people hiking in from Onion Valley over Kearsarge Pass).

Do you have any questions, comments, or concerns about Muir Pass? Leave a comment below or get in touch and let me know!